Astounding Science Fiction’s editor, John W. Campbell, once said that mystery and science fiction were incompatible genres. He stated that science fiction writers could invent convenient facts and technologies in an imaginary future to circumvent the deductive process. Hal Clement’s Needle (1950), Alfred Bester’s The Demolished Man (1952), and Isaac Asimov’s The Caves of Steel (1953), among other early works, demonstrate that science and mystery fiction mash-ups are not only possible, they’re amazing. Bester’s futuristic police procedural won the very first Hugo Award in 1953. Since then, many writers have explored the intersection between sci fi and mystery with great success.

Campbell took over as editor for Astounding Science Fiction—later called Analog Science Fiction and Fact—in 1937. Throughout the 1920s and ’30s, the Golden Age of Mystery Fiction, mystery authors, readers, even prominent detractors of the genre, agreed that mysteries were games played between the author and reader that should be governed by rules. Therefore, it’s no surprise that Campbell’s perception of mystery fiction seems closely tied to the conventions of the genre.

a human skull kept at Detection Club headquarters

During those years, Dorothy Sayers, Agatha Christie, and several other notable names from classic British mystery fiction, belonged to an organization of mystery authors called the Detection Club. The Club’s Oath asked new members, “Do you promise that your detectives shall well and truly detect the crimes presented to them, using those wits which it may please you to bestow upon them and not placing reliance upon nor making use of Divine Revelation, Feminine Intuition, Mumbo Jumbo, Jiggery Pokery, Coincidence, or any hitherto unknown Act of God?” Futuristic Technologies would neatly fit the list of gimmicks that can undermine the rules of detection and fair play that were obsessions of the Golden Age mystery writers. It’s easy to imagine Alien Races taking the place of super criminals and lunatics; forbidden culprits in the set of 20 rules developed in 1920 by S.S. Van Dine, the pseudonym of American Willard Huntington Wright, creator of the Philo Vance stories, which were written in the 1920s and ’30s very much in the classic scientific detective mode. But much has changed since the so-called Golden Age of mystery fiction, with police procedurals and hard-boiled detective novels joining forces with the classic cozies in expanding the genre’s reach into the readers’ imagination. Besides, as Asimov said, “science fiction is a flavor that can be applied to any literary genre, rather than a limited genre itself.”

Notwithstanding his conviction in sci fi’s unlimited possibilities, it’s no wonder that Isaac Asimov, a regular member of the mystery loving social club the Baker Street Irregulars, would be one of many talented sci fi writers to successfully challenge Campbell’s perception.

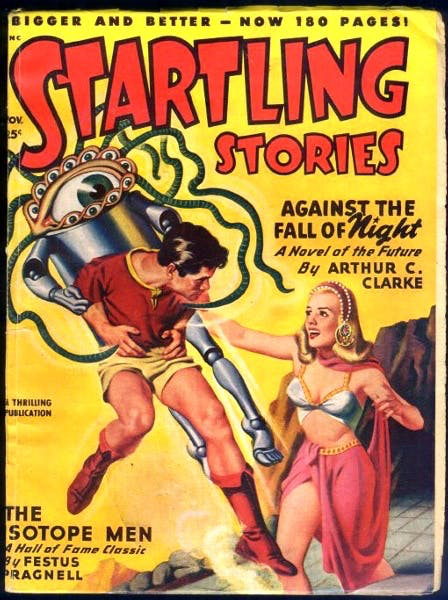

I fear I’m getting ahead of myself though. As I research the intersection of mystery and science fiction, and their development over time, I discovered a wonderful new set of possibilities. Jack Vance with his famous character, Magnus Ridolph—first in the “effectuator” characters’ line—clearly and delightfully inspired by Hercule Poirot, is the first science fiction writer to follow many of the classic rules that initially governed mystery fiction when he created The Unspeakable McInch, first published in Startling Stories, November of 1948.

Respecting many of Van Dine’s 20 rules for the mystery genre, Vance’s short story has a detective that never mentions a love interest. It has murders, besides thieving, and neither the detective nor one of the local investigators were responsible for the crimes. It even respects Van Dine’s hard line against literary flourishes—although possibly encouraged by the word count limitation of a short story—The Unspeakable McInch has no long descriptive passages, no side-issues, and no subtly worked-out character analyses. Vance applied other important conventions of the classic mystery, notably the antagonistic local authority: “Klemmer Boek, chaplain-in-charge of the Uni-Culture Mission, greeted him with little warmth—in fact seemed to resent his presence,” (Magnus Ridolph, Spatterlight Press 2012, 152).

Magnus Ridolph, a philosopher, describes himself as “a latter-day gladiator. Logic is my sword, vigilance is my shield,” he says. He’s hired by the Uni-Culture Mission to solve a mystery. Sclerotto City’s treasury safe has been robed many times by a McInch and everyone who has tried to discover whom that might be has ended up murdered.

Magnus Ridolph arrives on Sclerotto Planet where its two suns—one red, one blue—prompts the old gentleman to employ his handkerchief more often than expected in a sci fi story. I don’t remember seeing one in a sci fi before, but it certainly is in tune with Agatha Christie’s most famous detective. “Magnus Ridolph took a folded handkerchief from his pocket, patted his forehead, his distinguished nose, his neat, white beard,” and just like that I felt a warm familiarity (152). Ridolph’s characterization endearingly associates him with Hercule Poirot, who wouldn’t be caught dead without his handkerchief, not to mention untidy facial hair.

Sclerotto City is a cluster of misfit extraterrestrials and some humans crowded together cheek by jowl in clutter and squalor, where the only building of pretension is the tourist hotel. Yet, like in a countryside village, Boek says that what brings the tourists is “the way these creatures go about making a living Earth-style,” as the city has a “duly elected mayor, and a group of civic officers. There’s a fire department, a postal service, a garbage disposal unit, police force,” (157). Boek takes Ridolph around town visiting all suspects one by one in their respective places of work, hence creating a sense of fair play in the mystery game afoot. Clues are plainly stated and described, giving the reader equal opportunity to solve the mystery with Magnus Ridolph, provided the reader is shrewd enough to see it. After all, Jack Vance opens the story declaring that, “Mystery is a word with no objective pertinence, merely describing the limitations of a mind. In fact, a mind may be classified by the phenomena it considers mysterious…” (151).

To close the story properly, there’s the anticipated exposition at the end of the story, when Magnus Ridolph tells Boek, “I would like you to have Mayor—ah, Juju?… call a meeting this afternoon of the city officials. The city hall would be a satisfactory place. And at the meeting we will discuss McInch,” (185). As Ridolph reveals his detecting process in a logical sequence that is rational and scientific, and the who, how, and why becomes clear, there’s a definitive sense of… ooh.

My guess was wrong. To be fair, I was between two possibilities and in the end made the wrong call. Ridolph says that my guess was one of his own first suspects until he considered a certain sequence of events. I’ll take it. Anyways, the solution is as neat as Ridolph’s white beard. If you love mystery and are open to seeing quaint English countryside villages replaced by a faraway planet illuminated by two suns and “Kmaush… secreting pearls in their gizzards,”(159), in leu of charming old ladies, The Unspeakable McInch is for you. In an interesting twist that makes this short story particularly relevant in 2020, it’s Ridolph’s care with personal hygiene that saves him from an untimely death. Before stepping out of Sclerotto’s Uni-Culture headquarters to look around the city he says, “I’ll wear air-filters up my nostrils, and will spray myself with antiseptic. To complete my precautions, I’ll carry a small germicidal radiator,” (163). Now, that’s a timely read. I’m anxiously waiting for the germicidal radiator invention.

(I believe The Unspeakable McInch is the first sci fi mystery fiction mash-up, but maybe there’s an earlier one that I’ve missed. If so, I would love to hear about it.)